The Iowa caucuses were held yesterday, marking the official start of the 2012 presidential campaign. Dark horse Rick Santorum, a darling of social conservatives, came within eight votes of toppling front-runner Mitt Romney (each won 24.5%)—a result so close as to be reported a draw. Ron Paul also exceeded expectations, coming in third with 21.5%, followed by second-tier trio Newt Gingrich (13.3%), Rick Perry (10.3%) and Michele Bachmann (5%). If the results seem a bit anticlimactic that may be in part because the contest for the GOP nomination began almost a year ago, long enough for each of Romney’s very colorful competitors to enjoy a fleeting moment in the spotlight as the favorite Romney alternative. Many pundits predict that the GOP base will ultimately throw its weight behind Romney, who is generally viewed as the candidate who stands the best chance against President Obama in the general election. But for the moment the race remains uncertain. Despite his frontrunner status, Republican support for Romney has yet to break the 25% barrier—and his less-than-stellar Iowa performance gave comfort to those hoping for a spoiler.

At a series of televised GOP debates last year these five presidential wannabes and four others debated almost everything under the sun—everything except drugs and drug policies. Their silence about addiction and the drug war, which the Obama administration has called the nation’s no. 1 public health problem, may be the best indicator of the relative importance of the issue to Republicans. But if elected, one of them will have the opportunity to put into practice what they have so far only preached, which, taken together, is a remarkably diverse range of policies from legalizing all drugs to making importation of even modest amounts of marijuana a capital offense. With five of the six remaining contendors heading to New Hampshire or South Carolina for the next two primaries (Perry is returning to Texas to “reassess”), and the prospect of an Gingrich-led anti-Romney gangup increasingly likely, each candidate’s records and positions on drug-related issues now becomes need-to-know news for members of the recovery community.

Here’s how they measure up:

MITT ROMNEY: Critics of the former Massachusetts governor have rapped him for his flip-flopping on red-meat issues like abortion, gay rights and health-care reform, but since he first entered public office his position on substance and addiction issues has remained uncharacteristically consistent. As governor of Massachusetts in 2004 he introduced the popular “Melanie’s Bill.” Named after Melanie Powell, a 13-year-old girl who was killed by a drunk driver, the bill demanded stiffer penalties and mandatory sentences for repeat DUI offenders. The year after the bill was made law, the number of repeat drunk-driving arrests in the state fell by 50%.

Unlike most of his competitors, the former Massachussetts Governor has not shied away from taking a firm position on thorny drug issues. In the face of a nationwide trend toward legalizing the use of marijuana not only as a medical treatment but even for recreational use, the lifelong Mormon has denounced marijuana as “a gateway drug” and stood firm against pot-for-pain. But he has staked out a more critical position on the drug war, which was condemned as a failure by many experts last year on the occasion of its 40th anniversary. When a reporter asked him in 2007 if he thought America was winning the war on drugs, he said, “You know, uh, it’s been disappointing,” adding that while progress had been made in some areas, the war was a terrible drain on the economy. “We spend about $750,000,000 in Columbia alone, to help them eradicate the growth of cocaine there—we’re spending a substantial amount in Afghanistan to try and replace that crop,” Romney said. “We’re spending a fortune trying to keep drugs from growing around the world, and we’re not doing a terrific job.” Instead Romney has called for increased funding for prevention programs, including a nationwide anti-drug campaign on the model of Nancy Reagan’s “Just Say No.” “We have to be much more efficient about marketing this effort to our kids.” Romney may have more than a political interest in the subject. Bain Capital, his former investment company, owns a major interest in CRC, a company that owns 145 rehab facilities nationwide.

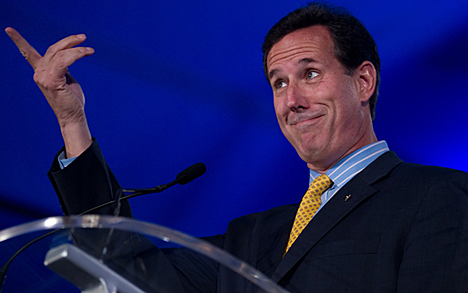

RICK SANTORUM: During his 12 years in public office, the two-term Pennsylvania senator has established a reputation as a vocal if conventional law-and-order conservative, advocating stricter punishments for a wide array of drug-related offenses. In 1999 he voted yes on a controversial amendment to stiffen federal penalties for manufacturing, dealing and possessing powder cocaine and other drugs. A strong booster of a military-style war on drugs, he voted in 1996 to increase federal funding for anti-narcotic operations and law enforcement at home and abroad. Not surprisingly, he is staunchly against the legalization of medical marijuana and has voted against legislation that increases funding for drug prevention and treatment. He’s also not above using addiction as a metaphor to malign his political opposition. As a Fox pundit and perennial campaigner, Santorum has likened labor unionsto “drug addicts whose drug is being taken away from them” and congressional supporters of “Obamacare” to “drug dealers.”

RON PAUL: The former Texas member of the House boasts what is generally viewed as the most transparent—and most radical—platform of the current GOP crop. In the course of a 35-year political career, the libertarian has distinguished himself by staking out positions far outside his party’s mainstream, even on loaded matters like drugs. Paul favors the legalization of both medical marijuana and cannabis for recreational use. He cosponsored, with Democrat Barney Frank, the States’ Rights to Medical Marijuana Act, and the Personal Use of Marijuana by Responsible Adults Act. In 2005 Paul also introduced the Industrial Hemp Farming Act, which would have made it legal for farmers to cultivate and harvest hemp for a variety of purposes. Paul has called to end the war on drugs—he repeatedly slammed the “lock ’em up” initiative as “racist”—and has gone so far as to call for the legalization of all of narcotics. In 1988, he said, “Prohibition doesn’t work. Prohibition causes crime,” a view that hardly endears him to the GOP’s socially conservative base. That may help explain his silence on these issues on the stump in Iowa.

NEWT GINGRICH: The former Speaker, Romney’s most potent challenger in the weeks leading up to the Iowa caucuses quickly crashed under a wave of negative advertising. As a Georgia congressman and, later, as a much-disliked speaker of the House, he espoused some of the most radical—and attention-getting—views of any elected official on many contentious social issues, particularly drug policy. The self-fashioned “ideas” candidate, he began his political career openly admitting that he had smoked pot in his youth. In 1982, during his third year as congressman he wrote a letter to the American Medical Association in pioneering support of medical marijuana, stating, “We believe licensed physicians are competent to employ marijuana, and patients have a right to obtain marijuana legally, under medical supervision, from a regulated source. The medical prohibition does not prevent seriously ill patients from employing marijuana; it simply deprives them of medical supervision and denies them access to a regulated medical substance.” Fourteen years later, in 1996, Gingrich’s ideology had undertaken a remarkable (even for a politician) about-face, penning the “Drug Importer Death Penalty Act,” which would have made the importation of 100 “usual doses”—or as little as two ounces of marijuana—to a mandatory sentence of life in prison without the possibility for parole, upped to the death penalty for defendants with a previous record of importation. The bill died in the Republican-led Congress.

During this same period, when Gingrich was riding high as leader of the “Republican revolution,” Newt recommended mass executions of those convicted of drug smuggling, to act as a deterrent to would be offenders. “The first time we execute 27 or 30 or 35 people at one time, and they go around Colombia and France and Thailand and Mexico, and they say, ‘Hi, would you like to carry some drugs into the US?’ the price of carrying drugs will have gone up dramatically,” he said. Startling hyperbolic rhetoric comes easily to Gingrich, and the Republican establishment lined up before Iowa to say that he’s temperamentally “unfit” to occupy the Oval Office. It’s worth noting that Gingrich has not only not renounced his most extreme views—he’s doubled down on the severity of his brutal enforcement stance.

RICK PERRY: The Texas governor fashions himself an old-school Christian conservative who doesn’t mince words when it comes to his “philosophy”—although tripping over words and other “oops! moments” in the debates cost him his early lead. His positions on many drug issues are somewhat more nuanced—and more consistent—than those of many anti-Big Government conservatives…except when it comes to hot-button social issues like abortion and gay marriage. He’s a firm believer in state rights (even threatening in 2009 that Texas might secede from the Union if Obama’s health-care reform became law) but also anti-drug and “tough on crime,” which, in practical terms, means that he’s OK if the hippies over in California want medical marijuana but legalizing pot is no-go in Texas. He acknowledges that penalties for drug-related crimes should be broader than just incarceration. “Western governors recognize the escalating costs of jail and welcome effective common-sense options within the criminal justice system that result in lessened drug abuse, healthier communities and decreased criminal activity,” he told a crowd in Iowa. He also favors bolstering border security to combat the drug trade and intensifying the war on drugs using paramilitary operations—a policy dramatically advanced under the Obama administration.

MICHELE BACHMAN: Of all the G.O.P. candidates, the Minnesota representative has the scantiest record on drug policies. Both her congressional and her campaign websites avoid any mention of the subject, and whenever she’s been questioned about her views on specific issues, like the legalization of medical marijuana, she has pointedly dodged or ignored the question. During a recent interview, a reporter asked her if she believed that state drug laws should take precedence over a blanket federal prohibition. “I need time to think about that,” Bachmann said. Her reticence may be strategic—as a hard-core evangelical conservative who, if pressed, would swear allegiance to the Gospel over the Constitution, many of her political positions put her at odds with many of her Tea Party constituency, who tend to favor individual liberties, states rights and limited government.

JON HUNTSMAN—the other Mormon candidate—is a former two-term governor of Utah and a US ambassador to China under Obama. Like Michelle Bachmann, he has a seriously scant record on drug related issues. He has never voted on a major drug related bill or publicly taken a position on the drug war; neither has he spoken for or against the federal status quo on drug laws. Jon Huntsman allegedly dropped out of high school to play in a teenage rock band called “Wizard.” Although the other band members were active drug users, they’ve publicly verified that Huntsman never personally indulged. Huntsman has never officially endorsed medical marijuana and no MMJ initiatives were launched in Utah during his time in office. But in an impromptu YouTube interview he claimed to support states’ rights on the issue. Current Utah law punishes possession of even tiny quantities of pot with jail terms of up to six months. As governor of Utah, Huntsman endorsed the “End Meth Now” campaign, a grass roots educational program teaching children the dangers of methamphetamine use. In a state address he said, “At the other end of the spectrum, we have worked like never before, at every level of government, to End Meth Now and stop the scourge of methamphetamine impacting our families and communities. We have more resources committed than at any other time to help fight this dangerous, destructive drug. I want my friends at the House of Hope, most of whom are young single mothers recovering from their addictions, to know the full meaning of that word: Hope.”

[UPDATE: 12 pm, 01/04: Rick Perry has announced that he will stay in the race, Michele Bachmann that she will end her campaign for president. —eds.]

Luke Walker is a reporter at The Fix.