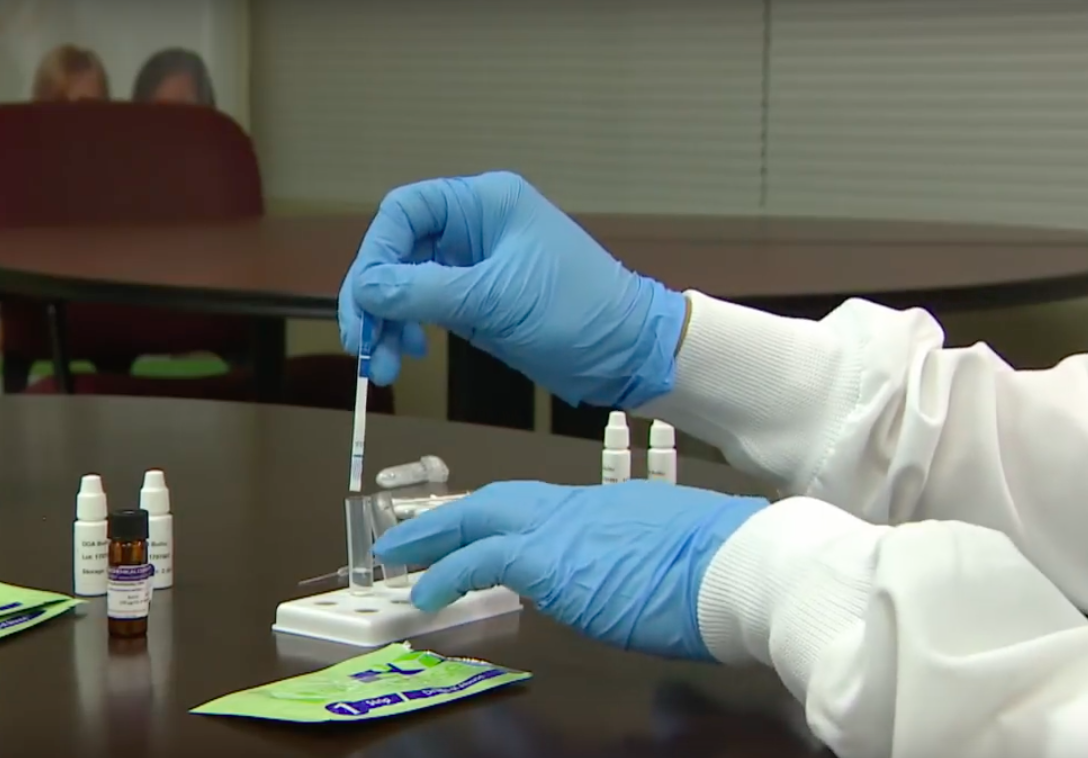

Fentanyl, the powerful opioid said to be responsible for exacerbating the opioid crisis, could be meeting its match: a $1 test strip that indicates the presence of fentanyl in street drugs.

A group of researchers wondered, if drug users had free access to these test strips, would they adjust their drug use to avoid dying from fentanyl?

They put together a research study, published in the International Journal of Drug Policy, that distributed test strips to 125 heroin users at a needle exchange program in Greensboro, North Carolina. They then distributed an online survey that revealed 81% of the heroin users had used the strips, with 63% reporting that their drugs tested positive.

Those who saw that their drugs contained fentanyl were five times more likely to adjust the way they used the drug so they would not overdose.

For example, they may have opted to snort it instead of injecting it, slowing down the rate at which it enters the bloodstream. Others opted to simply use a smaller dose.

The results are in line with a study by Johns Hopkins University researchers that found that users who preferred to inject their drugs did want to know if fentanyl was present, and would take its presence into account when using.

Proponents of harm reduction see the study as a positive step forward.

“Harm reduction at its core is a scrappy self-made movement,” said Daniel Ciccarone, a UCSF professor and study co-author. “Syringe exchange and naloxone peer distribution came out of this movement and have gone mainstream. But the [test strips] need an evidence base in order to become the next intervention in this legacy.”

Slowly but surely, test strips are making their way to being distributed alongside clean needles at needle exchanges. However, unlike clean needles, test strips are still considered paraphernalia and thus face some legal restrictions in their distribution.

The District of Columbia and Maryland have already adjusted their laws to allow the distribution of test strips, and advocates are confident other cities will soon follow.

But even if the legal jam were to be overcome, there’s another problem. That $1 price tag on each strip adds up. Critics say it’s more cost-efficient for users to simply act like all their drugs contain fentanyl instead of testing each and every dose, but that’s not good enough, said Jon Zibbell, RTI International public health analyst and study author.

“That’s like saying, ‘Assume everyone you have sex with has chlamydia,’” Zibbell said, suggesting that most people don’t act on a risk unless they have concrete evidence it’s real.

He hopes that the strips will lead to more cost-effective bulk testing methods, such as spectrometers that scan for fentanyl at every needle exchange site.